We asked Professor Luigi Cimarra, scholar and historian, to tell us something about the history of ceramic manufactures in Civita Castellana.

Production of ceramics in the area of Civita Castellana goes back a long way. The presence of the river Treja and various tributaries of the Tiber, in addition to nearby kaolin and fireclay quarries, allowed the inhabitants of Falerii Veteres, ancient capital of the Falisci, to acquire considerable expertise in this field: early crude manufactures were followed by more refined products that imitated oriental art.

During the 6th and 7th centuries BCE the sector experienced a crisis because of competition from the incomparable ceramics coming out of Attica: nevertheless, superior styling and rare personalizations allowed local manufactures to survive.

Even the Roman destruction of Falerii Veteres, which marked the end of Faliscan independence, did not interrupt the production of ceramics

Plate in painted ceramic.

Large vase in painted ceramic.

Etruscan Age, Museo Nazionale Archeologico.

Tarquinia.

Municipal laws from the Commune of Civita Castellana confirm that also during the Middle Ages ceramics played an important role in the local economy and the craft guild of the “vascellari” enjoyed considerable prestige. This tradition, unbroken for centuries, underwent a process of industrialization during the second half of the 18th century, when the Venetian engraver, Giovanni Trevisan, known as Volpato, obtained a license from Pope Pius VI to

excavate clay in the area around Monte Soratte, thus giving a strong impulse for the production of art ceramics to cater for the contemporary taste in classically styled ceramics. Volpato’s manufactures opened the way for a whole series of factories that sprang up in the region during the course of the 19th century (including Marcantoni in 1881).

In the early 20th century, a native of Civita, Antonio Coramuzi, began to produce sanitary ware using local raw materials. This marked the birth of the district of Civita Castellana’s specialty: many businesses evolved from artisanal workshops into industrial producers, so that raw materials had to be imported to ensure that the final product would have the highest quality. This proliferation of manufacturers (Sbordoni in 1911, Percossi in the 1920s which also produced tiles) and success, above all in Italy’s domestic market, stalled abruptly during the years of the Fascist regime when a policy of economic selfsufficiency banned imports of raw materials from abroad, resulting in a decline in production.

Giovanni Volpato,

herma with portraits

by Anton Raphael Mengs

and José Nicolás de Azara, 1785-1798.

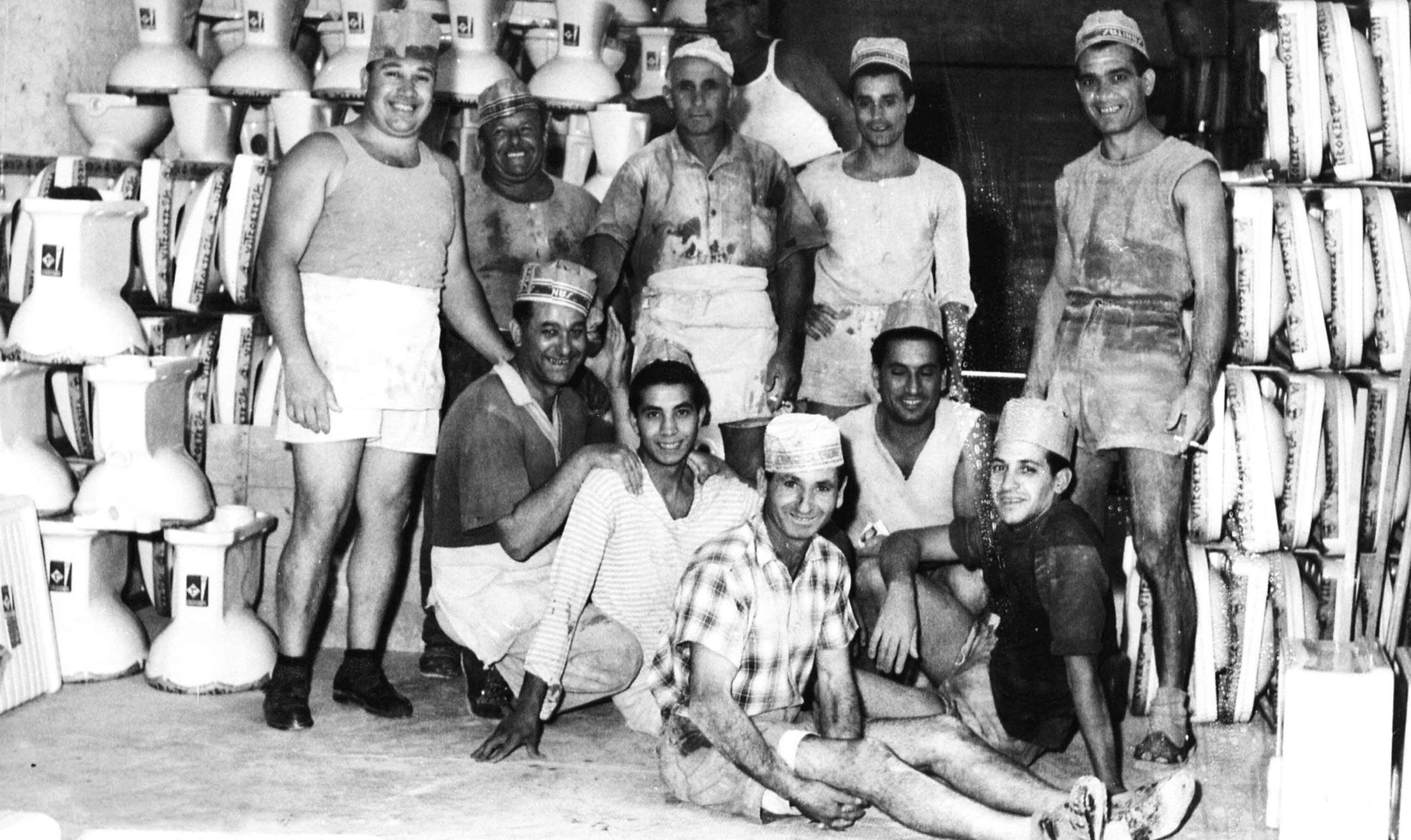

In the first decades after the Second World War Italy needed to rebuild its industrial fabric and the area of Civita Castellana was no exception. During the 1950s many workers were laid off because the companies that employed them were unable to deal with a financial and productive crisis. It was at this time that many ceramists decided to take over the factories from their owners: it was important for them not to lose the human capital of technical know

how and to continue to keep alive the “natural” vocation of an entire region. Company management was no longer done in the traditional style because now the factory owners were the workers themselves. This new system had the advantage of increasing production capacity because ceramists were even more directly affected by the success or failure of their work. Piecework became widely practiced.

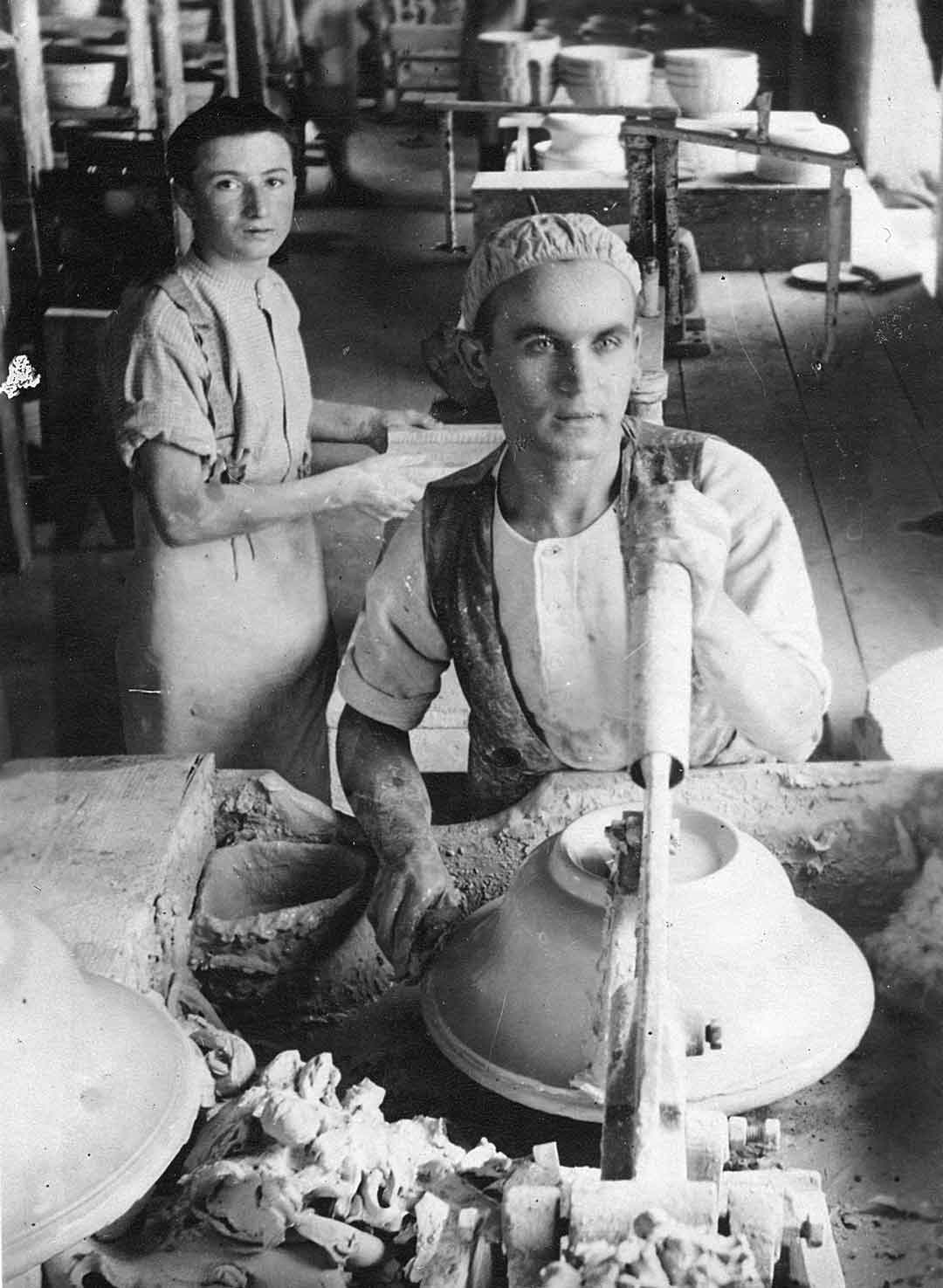

In the 1960s the construction boom in Italy was in full swing and demand for consumer goods became urgent. This demand was met thanks to fundamental innovations in the production cycle: the Tuscan furnace kiln which burns wood was replaced by the tunnel kiln which fires more uniformly and casting was introduced. Further innovations required new kinds of skilled professionals who now joined companies’ staffs, and workers already steeped in traditional techniques upgraded their skills, because they were the ones best suited to exploit the new know-how.

In the 1970s demand was very strong and this led to a certain standardization of products towards the lower end of the market. Many nonspecialized workers were drawn to a sector in continuous expansion that promised work and high wages, but the effects of this unchecked growth were soon felt. In fact, in the following decade the crisis in the European market dealt a severe blow to many companies that were unable to remain competitive: those that survived were the ones that were able to innovate and acquire market share in the Middle East.

Once again, profound change was needed so that this heritage would not disappear and it was technological innovation in the form of new casting machines and robots for glazing that helped the region’s manufacturing hub survive.

Today manufacturers in Civita are well aware that many emerging countries have become formidable competitors and they are seeking to make their companies more industrial, especially through new private capital investment. In 1982 the Centro Ceramica Civita Castellana was founded which brought together the sector’s micro, small and medium sized companies. Its aim is to carry out an ongoing search for resources while pursuing technological innovation, absolutely vital if we wish to meet the challenges of a globalized economy.

Civita Castellana is a region able to exploit artisanal know-how on the ground for the purpose of high quality, large scale production, in an area that has all the necessary resources to successfully face future challenges to the sector of ceramic production.